Systematic investigations at Tübingen on long-range aperiodic order started out from point symmetry forbidden in a periodic lattice and employ the dual cell geometry of a lattice of dimension n > 3.

With my research group at Tübingen since 1982 I systematically explored the projection method from an n-dimensional lattice Λ.

A first central idea was to fix the irrational section in Bohr’s theory by the selection of a non-crystallographic point group. Therefore the n-dimensional lattices were chosen such that they were compatible with a representation of a non-crystallographic point group G. The linear subspace E∥m for the quasicrystal, the irrational section according to Bohr, was then uniquely determined by decomposing the representation of the point group into its irreducible parts. A subspace E∥m with irreducible but non-crystallographic representation D(G) then carries the construction of the quasicrystal structure. To characterize this structure we employed the geometry of the lattice Λ and its projection to Em.

A second central idea of our analysis was the notion of duality in this geometry. We considered the geometry of high-dimensional Voronoi- or Wigner-Seitz cells of Em, defined by all points closer to a fixed lattice point than to any other one. The vertices of these Voronoi cells, called the holes of the lattice, form the centers of Delone cells dual to the Voronoi cells. For the concept of holes in lattices we refer to [8]. We studied the hierarchy of m-dimensional boundaries, 0 ≤ m ≤ n, abbreviated as m-boundaries, of both Voronoi and Delone cells associated with a lattice. We found that these boundaries admit a general notion of duality. Any m-boundary X of a Voronoi cell can be described as the intersection of the Voronoi cells for a finite set of lattice points. This finite set of lattice points has a convex hull of dimension (n-m). We showed that this convex hull is a dual (n-m)-boundary denoted as X*, from a Delone cell. This duality relation we took as a basis for the study of quasiperiodic tilings. For m=0, the 0-boundaries of Voronoi cells are the holes of the lattice. The duals to these 0-boundaries are precisely the Delone cells.

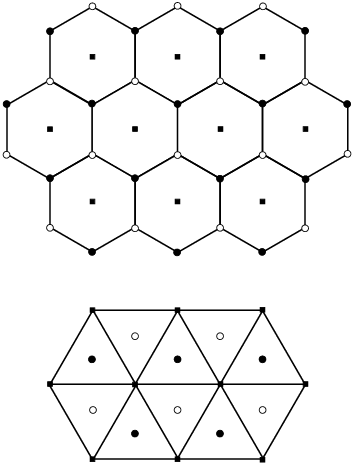

Example 2.3: Duality in the hexagonal lattice A2. We illustrate duality in Fig. 5 for the root lattice A2. Here we use the standard terminology of root lattices as given for example in [8].

Fig.5. Duality in the lattice A2. Upper part: The root lattice A2 has hexagonal Voronoi or Wigner-Seitz cells. centered at lattice points (black squares). Note that adjacent vertices (black and white circles) of the hexagonal Voronoi cell are inequivalent under lattice translations. Lower part: The dual is a tiling by two types of triangular Delone cells, centered at the vertices of the hexagonal Voronoi cells. Duality extends to all boundaries of complementary dimension: Any Voronoi cell is dual to a vertex of a Delone cell, any edge of a Voronoi cell dual to an orthogonal edge of a Delone cell, and any vertex of a Voronoi cell is dual to a Delone cell.

A particular case of duality arises for hypercubic lattices Zn in En. The Voronoi

cells are hypercubes, and the holes form a second hypercubic lattice, shifted

from the vertices to the centers of the hypercubes. Duality still work,

but there is no geometric distinction between Voronoi and Delone cells

and tilings based on them. This particular case appears already in the

projection of the Fibonacci tiling from the square lattice Z2  E2, Fig.

6.

E2, Fig.

6.

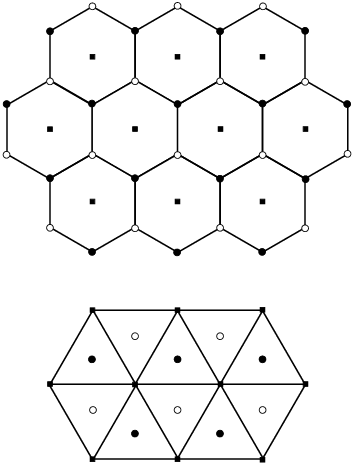

Fig. 6. The Fibonacci tiling. (a) The square lattice and its dual: The square lattice Z2 (lattice points black squares) in the plane E2. Its dual Delone cells are squares located at the holes (white squares). The irrational sections E∥1 are lines x∥ of slope τ. (b) Periodic tiling adapted to the irrational section: We devise a new periodic tiling by two squares (A,B) of edge length (τa,a). They are constructed locally by projecting dual pairs of edges from Voronoi and Delone cells X,X* (broken and dotted lines indicated on the right) parallel or perpendicular to the section x∥ and forming the product polytopes. (c) Quasiperiodic tiling on the irrational section: Any horizontal line parallel to x∥ is tiled by the vertical edges of the two squares (A,B) in a Fibonacci tiling with two tiles of length (τa,a). (d) Tile windows: The perpendicular vertical projections of the dual edges provide individual windows for the tiles. (e) Compatibility: A general periodic function fp on E2 can be defined on the two squares (A,B) since these together form a fundamental domain. The values of fp restricted to a horizontal line yield a general quasiperiodic function. If moreover the values of fp on (A,B) are chosen independent of the perpendicular coordinate x⊥, its quasiperiodic restriction to a parallel line becomes compatible with the Fibonacci tiling. Then the values of fp on the two Fibonacci tiles fix a compatible quasiperiodic function and so for them form a fundamental domain for the tiling. (f) Covering: The parallel projections D∥ of the Delone cells, black horizontal sections, yield a covering of the Fibonacci tiling. Any such projection comprises a fundamental domain for the tiling.

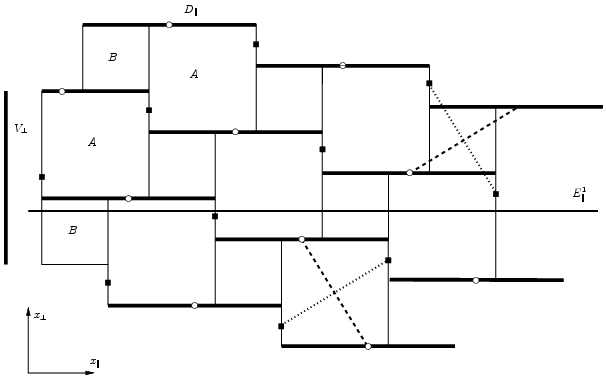

Example 2.4: Scaling in the lattice Z2: For the Fibonacci projection we describe the scaling property of the lattice Z2, compare [33]. First of all we write down in terms of two unit length orthogonal column vectors a basis matrix B = (b1,b2),

| (7) |

These two basis vectors connect a lattice point to two next neighbours (black squares) in Fig. 6. The upper and lower row of B describe the projections of the basis vectors (b1,b2) along the directions (x ∥,x⊥) in Fig. 6. Now it can be checked that the basis matrix B obeys the equation

![[ ] [ ]

- τ-1 0 1 1

0 τ B = B 1 0 .](index17x.png) | (8) |

The right-hand matrix multiplication describes a linear transformation with determinant Δ = -1 of the basis vectors with integer coefficients, that is a symmetry transformation of the lattice Z2. On the left-hand side, this multiplication is expressed in the form of a scaling of the basis vectors with scaling factors (τ,-τ-1) in the parallel and the perpendicular direction respectively. So the scaling in parallel space by τ can be interpreted as part of a transform of the lattice into itself. When this scaling is applied to the two original tiles of length (a,τa), it scales them into two tiles of length (τa,τ2a = (τ + 1)a). The scaled tiles can be decomposed into the original tiles. By repeating this scaling one can generate a Fibonacci string of arbitrary length. In any step of this generation, the frequency of occurence of each of the two tiles is given by successive /Fibonacci numbers.

We return to the general projection from a lattice. We found that, when m

becomes the dimension of the physical or parallel space E∥, this linear subspace is

tiled by the parallel projections of m-boundaries from Voronoi cells. The

perpendicular projections to the complementary subspace E⊥n-m plays an

important role in the dual projection technique: it determines the so called

windows of the objects. The role of a window in En for the tiling on Em is

defined by the rule: Whenever the irrational section Em within En hits a window

for a tile in En, the tile will appear in the tiling. Specifically, if the tiling

consists of parallel projections of m-boundaries say from Voronoi cells,

the windows for these tiles are the perpendicular projections of the dual

(n - m)-boundaries. The windows for the vertices of the canonical tilings

( , Λ), (

, Λ), ( *, Λ) projected from Voronoi or Delone cells, are the perpendicular

projections of the set of Delone cells and of Voronoi cells of Λ respectively.

Examples of vertex windows for the icosahedral tilings are shown in Figs. 10,

11.

*, Λ) projected from Voronoi or Delone cells, are the perpendicular

projections of the set of Delone cells and of Voronoi cells of Λ respectively.

Examples of vertex windows for the icosahedral tilings are shown in Figs. 10,

11.

Choosing as an alternative the projections of m-boundaries of Delone cells, E∥ is

again tiled by these. For given lattice and projection, the dual Voronoi and Delone

boundaries provide two alternative canonical tilings which we denote as

( , Λ), (

, Λ), ( *, Λ) respectively. The general scheme was developed in the doctoral

thesis of M. Schlottmann and published in [26].

*, Λ) respectively. The general scheme was developed in the doctoral

thesis of M. Schlottmann and published in [26].

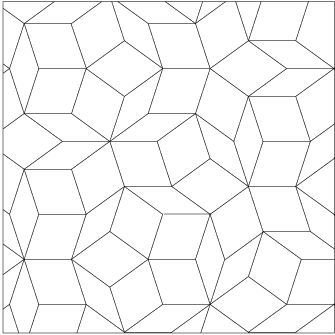

Fig. 7. Penrose rhombus tiling . The planar Penrose tiling ( ,A4) is formed by

two types of rhombs. They can be constructed as projections of 2-boundaries from

the Voronoi cells of the root lattice A4 in E4.

,A4) is formed by

two types of rhombs. They can be constructed as projections of 2-boundaries from

the Voronoi cells of the root lattice A4 in E4.

In [1] (1990), I studied with M Baake, M Schlottmann and D Zeidler the root lattice A4 in 4-dimensional space. We showed that the projection of 2D Voronoi boundaries yields the Penrose rhombus tiling Fig. 7, and the dual projection of Delone boundaries yields the Tübingen triangle tiling Fig 8. These tilings were used to model decagonal quasicrystals [29], [30] and were related to the Burkov model.

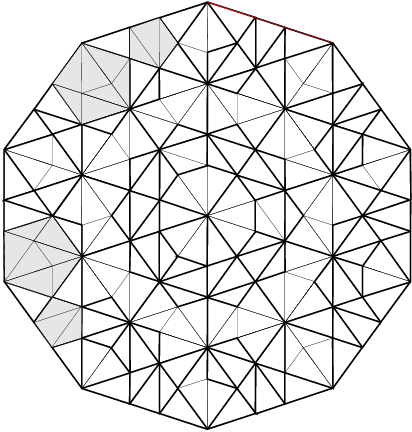

Fig. 8. Tübingen triangle tiling. (a) The planar Tübingen triangle tiling:

( *,A

4) is formed by two types of triangles, constructed as projections of

2-boundaries from the Delone cells of the root lattice A4 in E4. (b) Dual

projections: This tiling and the Penrose tiling shown in Fig. 7 exemplify dual

projections from the same lattice. (c) Pentagon covering: A covering of the

triangle tiling is given by two types of pentagons, projections of two types of

Delone cells from A4, shaded in the Figure. The four shaded pentagons together

comprise 20 triangle tiles in all possible orientations.

*,A

4) is formed by two types of triangles, constructed as projections of

2-boundaries from the Delone cells of the root lattice A4 in E4. (b) Dual

projections: This tiling and the Penrose tiling shown in Fig. 7 exemplify dual

projections from the same lattice. (c) Pentagon covering: A covering of the

triangle tiling is given by two types of pentagons, projections of two types of

Delone cells from A4, shaded in the Figure. The four shaded pentagons together

comprise 20 triangle tiles in all possible orientations.

The lattice A4 also has a scaling symmetry [1]. The two dual tilings ( ,A4),

(

,A4),

( *,A

4) admit two inequivalent Robinson-decompositions into triangles of the

shapes appearing in Fig. 8. From the scaling symmetry there result two different

stone-inflations of these triangular tilings. The stone-inflation for the Penrose

tiling is shown in Fig. 9. This stone inflation can be used to construct

quasiperiodic wavelets. The details are given in [31].

*,A

4) admit two inequivalent Robinson-decompositions into triangles of the

shapes appearing in Fig. 8. From the scaling symmetry there result two different

stone-inflations of these triangular tilings. The stone-inflation for the Penrose

tiling is shown in Fig. 9. This stone inflation can be used to construct

quasiperiodic wavelets. The details are given in [31].

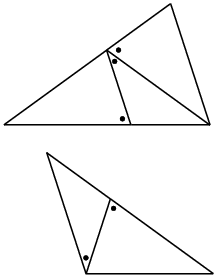

Fig. 9. Robinson decomposition of the Penrose tiling. The Penrose tiles can

be rearranged into two triangles of the same shape as in the triangle tiling

Fig. 8, but with different matchings. The orientation of any triangle is

marked by a black dot. The tiles admit a stone inflation: When scaled

by τ =  (1 +

(1 +  ), each tile can be decomposed into copies of unscaled

preimages.

), each tile can be decomposed into copies of unscaled

preimages.

Work on icosahedral projections and tilings was extended with Z Papadopolos and

D Zeidler in [27] (1992) by analyzing the root lattice D6, compare [8], also

denoted as the face-centered hypercubic lattice in 6 dimensions. This lattice is

inequivalent to the lattice Z6. The lattice D

6 can be identified by indexing its

diffraction pattern which belongs to its reciprocal lattice, the so called

body-centered hypercubic lattice. The lattice D6 occurs in stable phases of

AlMnCu. We constructed the six tiles for both the Voronoi- and Delone-based

tilings ( ,D6) and (

,D6) and ( *,D

6).

*,D

6).

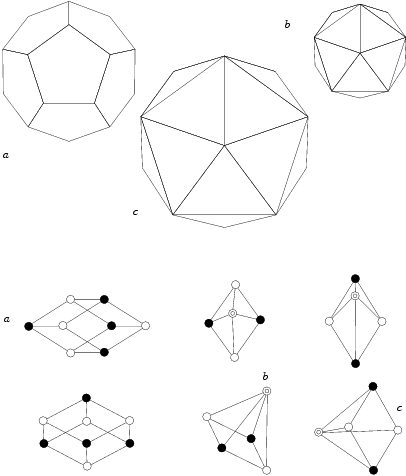

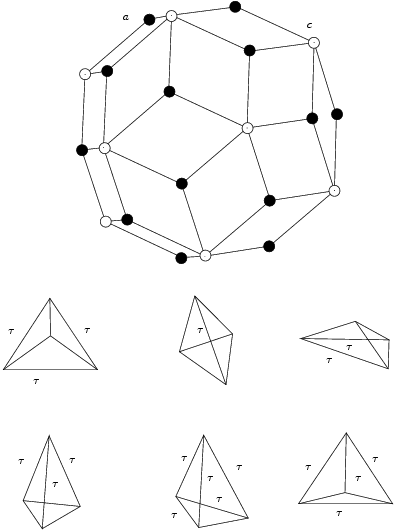

Fig. 10. Icosahedral tilings from Voronoi cells of the root lattice D6. Top:

The three types of Delone cells Da,Db,Dc of the root lattice D

6 in E6 project in

perpendicular space on two icosahedral and one dodecahedral polytope. They

form the window of the tiling ( ,D6) and of its three types of vertices. The

relative frequencies of the three types of vertices correspond to the volumes of the

projected Delone cells. Bottom: The tiles are two rhombohedra and four

pyramids on a rhombus base. Their vertices marked by black circles, double and

single circles are projections of the three types (a,b,c) of holes in the lattice.

,D6) and of its three types of vertices. The

relative frequencies of the three types of vertices correspond to the volumes of the

projected Delone cells. Bottom: The tiles are two rhombohedra and four

pyramids on a rhombus base. Their vertices marked by black circles, double and

single circles are projections of the three types (a,b,c) of holes in the lattice.

The lattice has three types a,b,c of translational inequivalent holes, that is,

vertices of its Voronoi cells, and hence three types of dual Delone cells. Under

icosahedral projection, the tiling ( ,D6) has the six projections of the

3-boundaries of Voronoi cells as tiles. These are shown in Fig. 10. We showed in

[28] that the tiling (

,D6) has the six projections of the

3-boundaries of Voronoi cells as tiles. These are shown in Fig. 10. We showed in

[28] that the tiling ( ,D6) is equivalent to a tiling constructed with methods of

scaling by Danzer [9]. This tiling in turn is related to a tiling constructed by

Levine and Steinhardt [35], [36] which in this way is shown to belong to the D6

module.

,D6) is equivalent to a tiling constructed with methods of

scaling by Danzer [9]. This tiling in turn is related to a tiling constructed by

Levine and Steinhardt [35], [36] which in this way is shown to belong to the D6

module.

Fig. 11. Icosahedral tiling from Delone cells of the root lattice D6. Top:

The Voronoi cell of D6 has as perpendicular projection Kepler’s triacontahedron.

Its vertices are marked as in Fig. 10. It forms the window for the tiling ( *,D

6)

and its vertices. Bottom: The tiles are six tetrahedra projected from

3-boundaries of the three Delone cells of D6. Their edges have two sizes scaled by

τ.

*,D

6)

and its vertices. Bottom: The tiles are six tetrahedra projected from

3-boundaries of the three Delone cells of D6. Their edges have two sizes scaled by

τ.

The second tiling ( *,D

6) based on duality has the six projected 3-boundaries of

the Delone cells, Fig. 11, as its tiles. The window for this tiling, the projection of

the Voronoi domain of D6, is again Kepler’s triacontahedron [16]. This tiling can

be related to the one by Mosseri and Sadoc [40].

*,D

6) based on duality has the six projected 3-boundaries of

the Delone cells, Fig. 11, as its tiles. The window for this tiling, the projection of

the Voronoi domain of D6, is again Kepler’s triacontahedron [16]. This tiling can

be related to the one by Mosseri and Sadoc [40].

For properties of root lattices we refer to [8]. A condensed description of the dual projection method is given in [33]. Up to now, all the tiling constructions for decagonal and icosahedral quasicrystals were shown by us to be related to the canonical tilings based on duality.